The pandemic may be loosening its stranglehold in many parts of the U.S. but its effects are still being felt across the country in the form of supply issues, logistic and transportation challenges, and labor shortages. The latter may be the most vexing of all for business owners who see the jobs coming back but not the workforce, a situation constraining the ability to ramp up operations as fully as desired. The pain appears widespread.

“Just about every company I work with or have spoken to is currently experiencing hiring challenges,” says Chad Sorenson, president of Adaptive HR Solutions, a Jacksonville, Fla., company providing customized leadership development, management training, performance management, employee relations and other solutions to a broad spectrum of industries.

“These range from not being able to find the right talent to realizing the starting wages of new employees are exceeding the wages of those who have been with the company for quite some time,” Sorenson continues. “The number of people in the workforce has shrunk since the pandemic. There isn’t one reason why the workforce is smaller, but rather each industry and geographic region have their own challenges. However, nationwide there are 1 to 2 million more job openings than there are people currently looking for a new job.”

This has resulted in an exceedingly difficult hiring environment, as Brian Richardson, president of L & A Tent & Event Rentals Inc., will attest. The Hamilton, N.J., company does about 100 weddings annually but concentrates on the educational and corporate event sectors and on ER response venues, among others. Before the pandemic the company had 37 non-management staff members. Now it’s operating with 15.

“We’re unable to even get people in the door to fill out an application,” Richardson says. “We’d hire an additional 10 people tomorrow if we could find them. We’ve had help-wanted ads up for more than three months and have had fewer than 10 applicants.”

Ed Skrzynski, owner and chief engineer of Marco Canvas and Upholstery LLC, is facing similar frustrations. Headquartered in Marco Island, Fla., the company provides textiles and metal fabrication solutions to the marine, shade and outdoor upholstery markets for government and commercial end users. Employees currently number 13, down from the 18 the company had before the pandemic struck.

Even before COVID-19, hiring could be challenging due to the lack of skilled applicants, says Skrzynski. But it’s now markedly worse: “No one seems to want a job,” he complains, adding that cross-training and automation have helped mitigate these shortages to an extent, although he needs more installers and sewers.

Competition and scarcity

Skrzynski attributes some of the workforce reluctance to government programs that provided enough financial assistance to allow many people to wait out the pandemic at home (although the ending of these benefits hasn’t yet resulted in a rush back to work). The fact that COVID-19 is still a concern may also be keeping potential employees away, he adds.

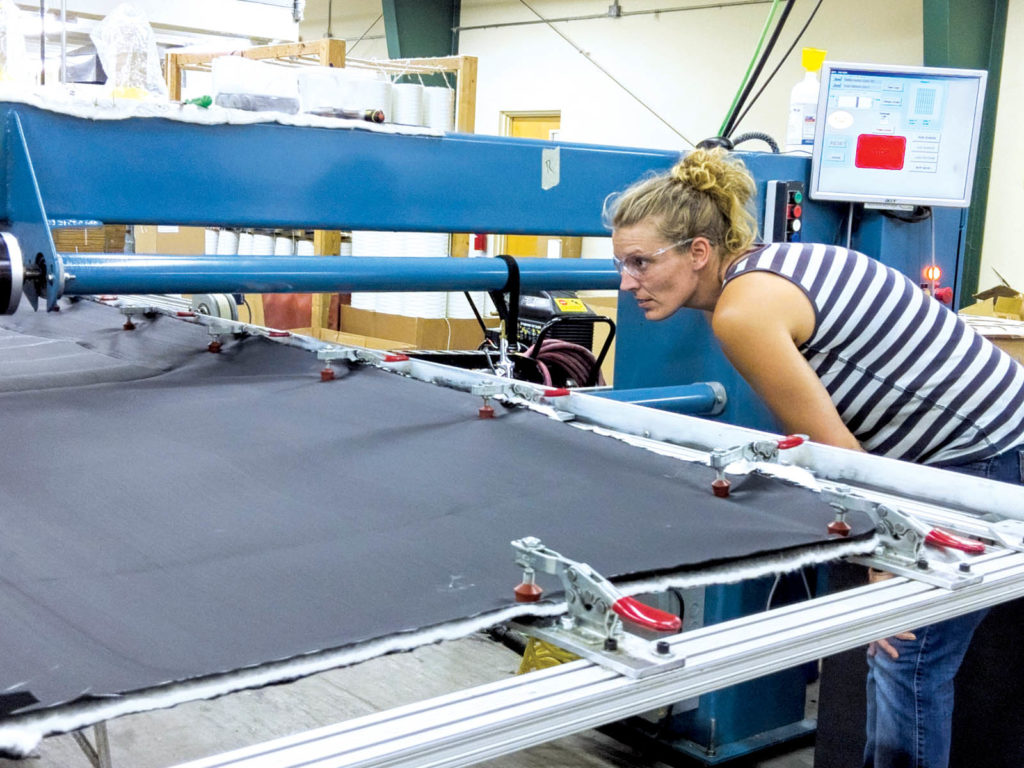

Intensified competition for employees is another issue, says Kathie Leonard, president/CEO of Auburn Manufacturing Inc. (AMI). Located in Mechanic Falls, Maine, the company makes industrial textiles (fabrics, tapes, ropes, etc.) for extreme-heat environments that are incorporated into products used for hot-work protection, mechanical insulation, safety garments and more. Markets include shipbuilding and repair, petroleum and power generation.

Hiring wasn’t always easy before the pandemic, Leonard says, also citing a dearth of skilled workers along with an aging workforce.

“But now, [it’s] even more challenging, due mainly to huge hiring bonuses offered by bigger employers at present,” says Leonard, adding that AMI is down five employees from the 52 the company had pre COVID-19.

“Also, the long layoffs some folks have endured have given them more time to think about what they want to do or not do,” she continues. “And there’s often hesitancy to take a manufacturing job they know nothing about. We need to make that process easier.”

AMI’s four-day-a-week manufacturing schedule proved a good strategy in the past for attracting workers, but less so now. The company also provides good benefits, such as a matching 401k, health insurance and a year-round lakefront company property available to employees. Even so, bringing in a second shift has proved taxing. However, these enticements have been effective in terms of retaining workers, says Leonard, adding that since COVID-19, the company has only lost one employee to a competitor.

Richardson believes in his case, the “extremely physical” nature of the work, the fact that much of this happens during weekends, and the long hours are behind his hiring woes.

“It appears to me that people are looking for a more personal and work-life balance,” he says. “Today, due to labor shortages across all industries, the applicant can be much more selective when it comes to picking a job.”

In response, Richardson says L & A Tent and Event Rentals is being choosier about the jobs it accepts, turning down those it may have taken two years ago. Increasing rental rates, achieving greater efficiencies through the use of equipment (which can also help reduce worker fatigue and burnout) and “shedding” unprofitable projects has actually improved the company’s bottom line.

“This year we’ve also retained an attorney who specializes in H-2B visas and are in hopes we’ll be able to use that avenue to add an additional 15 employees in 2022,” he says. “We’ve also had success previously by using a service that specializes in recruiting staff members from Puerto Rico.”

Finding and keeping

Labor shortages have also compelled Michael M. Woody, CEO of Trans-Tex LLC, to become more discriminating about the projects his company accepts. The Cranston, R.I., company is a finisher of narrow webbing, printing the webbing via dye sublimination in multiple colors, typically turning it into lanyards, pet leashes and collars, wristbands, headbands and shoelaces. Pre-pandemic there were 85 employees; this has dropped to 60.

Supply-chain issues in China—the company’s direct competitor—presented Trans-Tex with “some very large opportunities,” which it declined because they would have required the company to “at least double” its workforce in order to meet the deadlines, says Woody, explaining for now, the objective is to hire up incrementally.

Skilled cut and sew employees have always been in short supply, says Woody. Looking toward a longer-term solution to the labor issues affecting the textile industry overall, he has become involved with the Rhode Island Textile Innovation Network (RITIN), an association of R.I.-based textile companies, where he serves as chair. RITIN’s objectives are helping to close the skills gap; collaborating with colleges, universities and government agencies; providing problem-solving assistance to textile companies (this has also led to some internships and hiring); and creating business opportunities for members.

“RITIN has partnered with the Department of Labor and our local [Manufacturing Extension Partnership] to create cut and sew training programs,” says Woody. “We’re also in the process of trying to create a training program for machine operators. [A challenge] is that each company operates slightly different machinery. To solve that problem, we’re backing Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse’s proposed legislation that would pay a retiring employee to train his or her replacement.

“Attracting young workers isn’t the type of challenge that will be solved quickly,” he continues. “We need to change the hearts and minds of children and their parents, convincing them that the textile industry provides a solid career path.”

AMI is involved in a four-year, $60 million effort undertaken by the State of Maine to address workforce shortages through virtual training and an educational center, says Leonard, adding the company has just begun creating virtual training modules for its key operations. This team will include the production supervisor, department heads, current trainers, HR managers and, as needed, others to help in video production and uploading onto the virtual platform. AMI intends to produce at least 10 training modules, one for each department, says Leonard. Advisors from the community college system are helping with curriculum design.

Skrzynski uses automation—reverse engineering, 3D CAD, CNC cutting and plotting—to attract younger workers excited about learning new technology. As a result, five of the company’s 13 employees are between 19 and 26 years old. This has a feedback effect, he says, with the younger staff appealing to younger applicants.

He tackles labor shortages by casting a broad net, using agencies, social media, local papers and job posting/recruiting sites.

“Laborers tend not to have résumés and are likelier to be found through social media, local advertisements and temporary agencies,” he says. “Administrative, sales and technology jobs are more often found on recruitment sites and via headhunters.”

As for keeping them once hired, building close relationships between leadership and staff plays an important role in his retention strategy. This involves senior management proactively identifying and responding to employee issues, working alongside them, company barbecues, having one-on-one lunches (Skrzynski takes an employee to lunch weekly) and creating a “family-type” environment.

“People mostly quit because they don’t like their jobs or leadership. You’d think it was money, but job satisfaction and the ability to grow with the company is what keeps people around,” he says. “I feel you have to show a genuine interest in their personal and professional life and help them achieve their goals.”

Focusing on retention is smart, particularly since Sorenson expects hiring to remain difficult into 2022 as mammoth companies like McDonald’s, Walmart and Amazon are offering higher starting wages—a contagion that is spreading (Costco and Starbucks recently announced starting-wage increases).

“We know the old saying, it’s cheaper to keep the customer you have than it is to bring in a new one; the same holds true for employees,” he says. “Benefit programs, engagement training for managers and supervisors, pay-rate evaluations and workplace flexibility all play a role in retaining current employees.”

As for money, although it’s always among the top-five motivators, it’s seldom, if ever, number one, Sorenson says. As such, companies need to learn what motivates individual employees, as this is different for every person.

“The worst thing a company can do is develop a new employee benefit without first talking to employees. Too often I’ve seen companies spend time and energy developing a new program for employees only to see a 5 percent utilization. They developed something the employees didn’t want or see the value in.”

Pamela Mills-Senn is a writer based in Seal Beach, Calif.

SIDEBAR: Playing detective

Knowing why your current employees remain with you can help hone your retention and your recruiting strategies, says Chad Sorenson, president of Adaptive HR Solutions in Jacksonville, Fla. He recommends conducting “stay” interviews.

“Unlike a reactive exit interview with a resigning employee, a stay interview talks with current employees about why they joined the company and why they stay,” he explains. “Find out why employees like to work for you and use that to recruit new employees.”

Other tips he offers include proactively engaging employees since engaged employees tend to remain on the job, recognizing their hard work, and—very important—trying not to burn them out.

“This is hard, particularly when you’re short-staffed,” he admits of that latter suggestion. “But it will help retain employees. Extra pay isn’t always the answer—it doesn’t get them home any earlier. Sometimes it’s a thank-you and buying lunch for the team, or maybe it’s an extra PTO day.”

TEXTILES.ORG

TEXTILES.ORG