Everybody knows about inflatables. They’re the bouncy houses rented for kids’ birthday parties, or the big blow-up gorilla that the local car dealership uses to attract customers. The real growth in the use of inflatable technology, however, is in much more serious (and practical) applications—even if they aren’t nearly as visible to most of us.

It’s true that inflatable structures are not new in settings where their inherent advantages are well-known. “They can be used in applications where there are limitations to the size, shape, weight or other characteristics of steel or other hard good materials,” says Toby Cummings of Warwick Mills Inc., a New Ipswich, N.H., company that develops and manufactures fabrics and materials for inflatable structures. But more and more, what’s attractive about inflatable structures is their ability to protect both people and property against the dangers of the modern world, natural and otherwise.

For example, Dynamic Air Shelters in Calgary, Alberta, Canada, builds inflatable structures for workers and equipment in harsh environments, which includes field hospitals, military command posts and work sites. Their convenience in such settings is an asset, but what makes them especially valuable these days is advancements in their protective abilities, given their exposure to explosions, either accidental or intentional.

“We’ve developed inflatable structures that completely eliminate shock waves,” Dynamic Air Shelters founder Harold Warner says. “An inflatable is able to capture and transmit the energy, but if a steel building is hit with a shock wave, it’s coming down.”

Protecting what’s inside

The key in such situations is the ability of the structure to protect what’s inside against a blast, according to Warner, whose early experience with inflatables was creating and flying hot air balloons—and setting long-distance flight records in the process.

The energy is captured in the air columns of the inflatable structure and transmitted over the top and into the ground on the other side, Warner explains. That’s not what happens with a steel building.

“When a shock wave hits the outside of a steel building, it causes a deflection, a deformation of the wall,” Warner says. “That propagates a new wave inside that will bounce back and forth like a pinball machine. It can bounce a fire extinguisher back and forth at 500 meters a second. With a higher level blast, it’s worse inside than out.

“If given a choice of being hit by a fire extinguisher traveling at 500 meters per second or a pickup truck traveling at 50 miles per hour, the truck would be the better choice,” he says.

But the fact that a structure is inflatable is not why it’s able to withstand a high-velocity impact, according to Warner. “The reason it’s blast-resistant is because of the way we harness the energies acting on the inflatable. It’s the resilience,” he says.

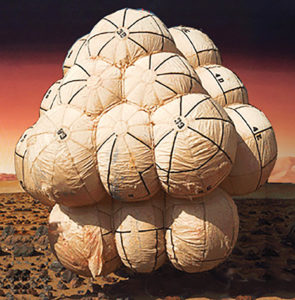

Dynamic’s shelter system is made of a low-pressure air beam support structure, a heavy-duty waterproof fabric shell and liner, and a flexible moveable exterior fabric barrier that surrounds the perimeter.

Keeping workers safe

Dynamic provides shelters for numerous applications, including hangars, camps and machine shop warehouses in war zones. However, part of the development of the shelters has come as a result of the increasing attention paid to the need to protect workers from plant site dangers, triggered in part by the well-publicized Texas City, Texas, oil refinery explosion in 2005 that killed 15 people and injured nearly 200 others.

In 2014, the American Petroleum Institute (API) codified protection standards, adopting guidelines for managing the risks of explosions, fires and toxic material releases to on-site personnel located in tents. Dynamic notes the fact that its products are considered one of the best solutions to meet API’s standards.

ILC Dover, based in Frederica, Del., is no stranger to inflatables. It grew out of a company that produced flexible attack boats, life rafts and canteens for soldiers in World War II, and is perhaps best known for producing the space suits for the Apollo and Skylab missions. “People don’t think of space suits as inflatables, but they are,” says Alan George, the company’s technical sales specialist.

ILC Dover is still in the space suit business, but produces flexible containment solutions for a variety of industries, including pharmaceutical and biopharmaceutical manufacturing, personal care, food and beverage, chemical and health care, as well as aerospace applications.

According to George, one of ILC Dover’s inflatable products, the Resilient Tunnel Plug (RTP), is a tool to protect rail, automotive and other tunnels from threats, including water, “but it was developed with the Department of Homeland Security Science and Technology Directorate specifically

to protect from flooding caused by a terrorist bombing, or to contain a chemical biological warfare attack.”

George compares the RTP to an automotive airbag system in the way it is held in a small container and is pressurized to shape when an event occurs. The barrier is created when internal pressure exceeds the external water pressure. Like many inflatables used in critical situations, the exterior of the RTP is made of Kevlar® or Vectran®.

Gathering intelligence

ILC Dover also produces commercial airships seen at sporting events, but the technology has growing importance in the area of national security, George says. For example, the company has developed aerostats that carry surveillance radar up to 15,000 feet while connected to the ground with a single tether. They’re used for various intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) applications, including southern border protection.

None of the sophisticated applications for inflatables would ever have come to pass, of course, if they didn’t offer characteristics that give them a leg up on more conventional structures.

One of those characteristics, not surprisingly, is portability, characterized by easy storage, setup and takedown.

ProPac Inc. of North Charleston, S.C., specializes in emergency preparedness supplies and produces inflatable structures of various sizes that are designed to connect together to make mobile hospitals, emergency operation centers and even homeless shelters. According to Skip Stephenson, ProPac’s director of sales and business development, the company’s largest structure, at 22 feet by 42 feet, can be rolled up small enough to fit on a pallet.

“With an inflatable that is 11 feet by 16 feet, a single person can set it up in under 10 minutes, and the inflation itself takes less than three minutes,” Stephenson says. “You can have a 20-bed mobile hospital operational in less than 30 minutes.”

Power is not necessary to fill the structure with air, he adds—just a high-capacity self-contained breathing apparatus bottle.

With ILC Dover’s tunnel plug system, the RTP is stored at the point of use “so you don’t need the time to move it, or the manpower,” George says. “It’s a lot faster than when you have metal components that need to be kept somewhere else. And ‘faster’ is important when you’re protecting critical assets.”

Increasing strength

Advancements in fabrication technologies also make inflatables stronger than they used to be, which is especially valuable in those applications where it’s difficult or impossible to use hard good materials.

“What’s critical is that we have techniques that allow us to seam fabrics at the parent strength of the yarn, so the inflatable acts as if there is no seam,” Cummings explains. “In some cases, just a few pounds of strength per fiber, multiplied out by the size of the inflatable that Warwick is able to preserve in processing, can be damaged in other facilities, causing the material not to

work for the end application.

“Some of our Vectran fabric made with 1,000-denier or higher yarn can achieve over 1,000 pounds an inch for tensile strength,” he adds. “Vectran, when laminated with TPU [thermoplastic polyurethane] to be airtight, can hold very high pressure.”

Bouncy houses and blowup gorillas may be fun, and garner most of the public’s attention. But they’re not what’s driving the industry.

Jeff Moravec is a freelance writer from Minneapolis, Minn.

TEXTILES.ORG

TEXTILES.ORG