The Canadian Printable, Flexible, Wearable Electronics Symposium (CPES2017) was held on the outskirts of Toronto in May this year. Buildings, and smart buildings in particular, were a hot topic both in presentations and in the poster exhibition that accompanied the three-day event. Ronald Zimmer, president and CEO of the Continental Automated Buildings Association (CABA) set the scene with his keynote presentation on the connected home and intelligent buildings.

CABA is comprised of industry leaders with the mission to promote the use of integrated systems as well as home and building automation worldwide (though with a strong North American presence). By its nature, the organization attracts a broad range of stakeholders, with membership ranging from governments, associations and academic institutions to energy utilities, builders and manufacturers—and virtually every other industry involved in making smart buildings a reality. While much of the organization’s work revolves around stakeholder interests, dissemination of information through lectures and highly focused reports reaches an even larger audience and starts conversations and speculation about future industry directions, such as the role of smart and advanced textiles in intelligent buildings.

Smart building basics

What are intelligent buildings and connected homes? Zimmer describes them succinctly as those that are equipped with some form of Building Automation System (BAS), controlled using a distributed computer network via Ethernet and wireless communication. The system has an impact on all aspects of the building, from heating and ventilation to security and fire systems. There are three drivers behind intelligent buildings, and they are linked: environmental benefit, user comfort and cost benefit.

More efficient use of energy is better for the environment as well as more cost-effective for users and residents. More responsive systems can tell when a room is occupied and provide necessary heat and lighting; the system can also tell whether there is one person or three hundred people present and adapt accordingly. It also makes it much more comfortable for the occupant, effectively providing a microclimate. Textiles, and smart textiles in particular, are an integral part of this vision for future living.

Going back to the early commercialization of smart materials and systems, textiles functioned mainly as a flexible conduit for the technologies—without being inherently smart themselves. In structural terms, earthquake and disaster monitoring was an important field of research and development, but is that still the case today? Zimmer comments on companies in California doing some great work in this respect, with detection devices that give two minutes’ advance warning that is especially useful for utilities. But their ability to warn occupants of invisible risks is vital. Zimmer explains, “With kids increasingly sensitive to environmental issues such as mold, they can be contaminated through ventilation systems so that it is not noticed.”

One of the benefits of incorporating sensors into textiles is that they are not visually intrusive and can blend with interior decoration. He gives the example of Georgia Tech’s home of the future, in which sensors are incorporated into the carpet. In this way the elderly, for example, can be monitored for falls and location using geopositioning, but achieved in a much less invasive way than conventional camera surveillance.

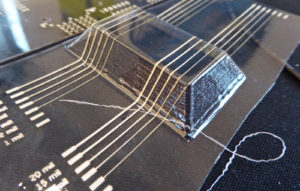

According to Zimmer, health care is the big driver for the use of textiles in intelligent buildings: “With the emergence of the Internet of Things (IoT) we are now able to monitor non-technological objects such as pills, or check if there is water in the basement.” Insurance companies, especially, are extremely interested in developments of this kind, and in the wider potential of IoT. “What we are seeing is a massive explosion of IoT as we move towards unconnected objects with multiple embedded sensors,” says Zimmer. Sensors and connectivity are driving this trend in the intelligent building and smart home, with textiles in the form of curtains, carpets and wall coverings as ideal conduits. Unlike the situations in the early 1990s, the smart technology is now more fully embedded into the textile—the fabric itself can be the sensor.

No more sick buildings?

The key drivers in the sector, Zimmer says, are energy, wellness and comfort. Smart textiles provide a more aesthetic housing of the technology than black boxes or surveillance cameras. But one of the biggest hurdles is persuading architects and builders of the true value of intelligent buildings.

Where every dollar counts in buildings and their use, energy cost savings is a persuasive argument, as is higher employee productivity. If people enjoy working in a building, absenteeism goes down. We have seen the impact of bad buildings and people suffering from “sick building syndrome,” so a building that makes people feel better and more comfortable will encourage them to stay.

As Zimmer puts it, “We believe that employee productivity is the route to go.” He also sees no reason why we should not have zero-energy buildings; perhaps not with existing buildings, but for new construction it should be possible. In 2007, the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) adopted the aspirational goals that all new residential construction in California will be zero net energy by 2020.

CABA does not have any textile manufacturers as members yet, but acknowledges that it is increasingly on the radar for a number of member companies for applications relating to aging, health and well-being—where wearables already have a natural and increasingly important role. Zimmer asserts that it may need government and insurance companies to forge through developments in the sector to draw together the different stakeholders.

There are broader advances in technology that are affecting building construction and beginning to converge with smart textiles in particular, notably Big Data and the IoT. Zimmer focuses on wearables and their role in intelligent buildings as a more effective means for humans and their environment to communicate more fluidly. In this sense, smart textiles for buildings cannot be considered in isolation; we need to adopt a more holistic view of technology and how each element is part of a much larger ecosystem.

When smart materials were first introduced to the commercial sector, they were referred to as “smart materials and systems.” The “systems” part has been dropped over the years, possibly for convenience, but at the expense of accuracy. Smart homes and intelligent buildings in particular rely on systems, and there is a strong argument for bringing back the original descriptor in full to communicate the function and the great potential for these technologies in the built environment.

What’s next for smart homes and intelligent buildings? According to Zimmer: “From my standpoint, I would like to see industry really embrace interoperability and open standards. Too often companies want to control the market to their benefit, so their system will not work with others. The consumer should never have to worry that they should not buy a device because it will not work with another. The automotive industry has worked this out; so can we.”

Marie O’Mahony is an industry consultant, author and academic. She is the author of several books on advanced and smart textiles published by Thames and Hudson, and a visiting professor at the Royal College of Art (RCA), London.

TEXTILES.ORG

TEXTILES.ORG