Italian architects and German engineers create a dynamic fabric structure for the Palace of Congress conference center

“Make no little plans; they have no magic to stir men’s blood and probably will themselves not be realized. Make big plans; aim high in hope and work.”—Daniel H. Burnham, American architect

No one could accuse fascist leader Benito Mussolini of making little plans. In the 1930s the dictator of Italy had chosen a stretch of land south of Rome, the capital city, as the site for the 1942 World’s Fair to celebrate 20 years of fascism. Designated the Esposizione Universale Roma (EUR), the planned expansion of the city toward the southwest was to directly link Rome to the sea, some 30 km (18.6 miles) away. Key to the plan was a major highway, originally dubbed Via Imperiale, as part of a five-year effort to prepare for the World’s Fair.

A major interruption—World War II—put a stop to that project and to the World’s Fair, but the highway was finally realized for the 1960 Olympics and renamed Via Cristoforo Colombo. Now the longest Italian road within the borders of a single municipality and considered the grandest in Italy, Via Cristoforo Colombo is the driver of development and construction for many large-scale projects like the Central Archives for the Italian state, numerous commercial buildings, and a new major conference center—Rome-EUR Palace of Congress—which dominates a crossroads at the center of the EUR district. The EUR SpA is actually a development organization jointly owned by the Italian Ministry of the Economy and the Rome municipality.

Completed last October, the Palace of Congress was designed by internationally acclaimed Italian architect Massimiliano Fuksas, director of Fuksas Studio, as a simple ensemble of three major architectural masses, which he calls “Theca”, “Lama” and “Nuvola.” The ensemble creates a complex relationship with the public spaces surrounding the center’s grounds, the spaces of the surrounding landscape or urban context, and the spaces contained within. In this “trifecta” of parts, Fuksas has placed flexible exhibition spaces, conference and meeting rooms, a 1,800-seat auditorium plus support spaces, and a 439-room hotel. All of this surmounts a 600-car parking garage underneath, making a total building area of 55,000 square meters (592,000 square feet).

Fuksas designed a similarly organized large convention center, the Australia Forum, several years ago for Canberra, the capital of Australia, and similarly located it in the heart of an urban setting with comparably sized volumes that emphasize transparency and openness toward the surrounding landscape. Here, as with his Rome project, and likewise with his design of the National Archives of France in Paris, the designer favored three major functions placed on three levels.

In a review for Architect magazine, the noted architectural critic Joseph Giovannini described Fuksas’ Paris project in terms that could easily apply to the Rome-EUR project: “For all its conceptual clarity, the simplicity is deceptive. What appears at first to be a rudimentary Cartesian layout that builds off the grid seems, at moments, to introduce chaos theory.”

Designing in threes

With the Rome-EUR convention center, the three elements—Theca (meaning case or envelope in Latin), Lama (blade in Italian), and Nuvola (cloud in Italian)—are each given a different shape and dominant material. The blade thin hotel is treated as an independent and “autonomous” glass structure functioning on its own but in relation to the other parts.

The Theca is a double-glass façaded rectilinear container for the Nuvola, which Fuksas describes as the “heart.” “The ‘Cloud’ represents the heart of the project,” says Fuksas, “Its construction within the box of the Theca underlines the juxtaposition between a free spatial articulation, without rules, and a geometrically defined shape [of the box].”

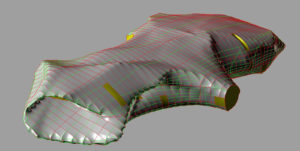

The undulating and oddly shaped Nuvola is clad in milky white silicon-coated glass fabric, filling the interior space of the Theca to the point of almost touching the outer glass walls. Floating in the upper half of the interior volume, the cloud form touches down to the main floor at only one point, with one side protruding to reach two upper level bridges to the rest of the complex. Visitors enter into the cloud via these bridges or from stairs underneath.

The main space within the cloud is taken up by the auditorium, the foyer areas where snack bars are scattered throughout and a café. The supporting structure of the Nuvola is an undulating steel network of closed-webbed ribs that, despite their irregularity, follow strict adherence to an unrelentingly orthogonal grid. It is this contrasting physical pattern—amorphous, flowing forms against a 3-D grid—that sets up tension and creates interest. It’s an apt metaphor; the fabric is tensioned tight against the steel ribs. Contrast is also created between the glass box (Theca) and glass fabric (Nuvola); between the inside and outside spaces; and between the transparent exterior and translucent interior.

Shape finding

Shape finding

To arrive at the unusual cloud shape, the architects collaborated with Italian professor Massimo Majowiecki, who is noted for his expertise on form-finding in fabric structures and complex constructions. “The cloudscape was cut virtually in all three axes at firmly defined distances into slices,” says a press release by formTL, the consultant engineers, “and the resulting frame was built of steel, by Cannobio, in charge of the realization of the skin.” The complexity of the shape proved to be a fabrication challenge during planning due to the fixed axial spacing of the substructure. “Greater or closer spacing would have been advantageous with regard to creating the effect of lightness of a cloud,” says formTL.

To handle the variable tension points, formTL adapted the tension of each panel of fabric to each individual situation and developed a special bracketing system. Brackets are mounted on the steel ribs and are height adjustable, enabling fine tuning so that the taut skin membrane will not touch the steel ribs except where attached to the brackets.

Celebrations of the new exhibition center were held last fall, and the Nuvola floated cloud-like both day and night as a “luminous body that can be seen from far away.” Nice plan!

Bruce N. Wright, AIA, is a registered architect, writer and educator who frequently contributes to Fabric Architecture, Specialty Fabrics Review, and Advanced Textiles Source.

To make sure the fabric skin matched the architect’s conception, individual cutting patterns were kept with as few seams as possible between ribs. “Because of its amorphous shape, the skin consists of 2,763 different cutting patterns which were assembled into 607 individual panels,” says a press release from formTL. “The brackets and clamping lines along the steel ribs are also individually shaped, posing a challenge in terms not only of engineering but also of logistics.”

TEXTILES.ORG

TEXTILES.ORG